A recent decision handed down by the United Nations Human Rights Committee (CCPR) has once again condemned Ireland for maintaining laws that protect the right to life for the unborn. The decision is now the second time in the last year that the CCPR has attempted to intervene on Ireland’s national sovereignty, pressuring the country to legalize abortion.

The New York-based abortion advocacy law group, the Center for Reproductive Rights (CRR), petitioned the CCPR on behalf of the alleged victim, Siobhán Whelan. Whelan had traveled to the United Kingdom in 2010 to abort her child at 20 weeks gestation after her child had been diagnosed with a tragic fetal disability and had been declared “incompatible with life.”

Whelan, via her legal counsel, petitioned the CCPR in 2014, alleging that Ireland’s pro-life laws subjected her to “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment” and “intense stigma for terminating her pregnancy.”

The CCPR sided with the complainant, finding Ireland to be in violation of several articles of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights including a violation of Whelan’s right to privacy, discrimination on the basis of sex, and “cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment.”

The CCPR directed the Irish Government to pay Whelan compensation fees and to provide her with any needed psychological treatment. The CCPR also instructed the Irish Government to legalize abortion by whatever means necessary, even if such remedy requires a change in Ireland’s Constitution.

The CCPR leveled the same accusation against the Irish Government last November in a similar case brought forward by Amanda Jane Millet and the CRR. The Irish Government agreed to pay Millet €30,000 in reparation for the alleged offenses.

The decision handed down by the CCPR this month is only the most recent instance of the onslaught of pro-abortion activism heaped on Ireland in recent months.

Numerous pro-abortion nongovernmental organizations, like Amnesty International and the Irish Family Planning Association, International Planned Parenthood Federation’s Member Association in Ireland, have lobbied heavily for the legalization of abortion in Ireland.

Several multilateral institutions have also attempted to sway the debate. Earlier this year, the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW)—a human rights treaty-based body similar to CCPR that monitors the implementation of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women—demanded that Ireland legalize abortion in cases of rape, incest, fetal disability, and physical and mental health of the mother.

This past March, Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights, Nils Muižnieks, also called on Ireland to legalize abortion under the same cases. Muižnieks has called for Ireland to legalize abortion in spite of a decision handed down by the Council of Europe’s European Court of Human Rights in 2010 which upheld Ireland’s right to keep abortion illegal in the landmark case A, B and C v. Ireland. As recently as December of 2014, the Council of Europe found Ireland’s abortion laws satisfactory.

Abortion is illegal in Ireland except to save the life of the mother. The Eighth Amendment to Ireland’s Constitution guarantees the right to life for the unborn and “as far as practicable, by its laws to defend and vindicate that right.” The Eighth Amendment was ratified by popular referendum in 1983 with the approval of over two-thirds of the voters.

However, various referenda and judicial decisions have since gradually eroded Ireland’s laws defending life.

Click here to sign up for pro-life news alerts from LifeNews.com

In 1992, the Supreme Court of Ireland ruled in Attorney General v. X that the Eighth Amendment did not preclude mothers from terminating the life of their unborn child in cases where it is determined that she is at-risk for suicide. A pair of popular referenda that same year amended the Constitution to prohibit the state from protecting the interests of the child through limiting information about the availability of abortion in other countries or by preventing women to travel abroad for the express purpose of aborting their child. As a result, several pro-abortion organizations in Ireland have since routinely facilitated women in traveling to other countries to abort their unborn children.

Recent intense pressure from pro-abortion advocates both in Ireland and abroad have forced Irish lawmakers to move forward with a referendum on the Eighth Amendment. Earlier this month, Ireland’s new Prime Minister Leo Varadkar announced before the Dáil (Ireland’s main legislative assembly) that his government will allow a repeal referendum on the Eighth Amendment to be placed on the ballot next year.

The CCPR alleges that Ireland’s pro-life laws are not in line with the state’s obligations under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR).[1] However, the assertion is questionable as there does not appear to be any obligation for states to legalize abortion under the treaty nor under the standards of international law.

What the ICCPR says about abortion

The ICCPR is a United Nations human rights treaty that was adopted by the General Assembly in 1966 and came into force ten years later after the required number of countries had ascended to the treaty. Because ICCPR is a treaty, countries that have either ratified or acceded to the treaty (i.e. countries that are “state parties” to the treaty) are legally bound to observe it. Almost every United Nations recognized entity has become a state party to the Covenant.

The CCPR was created by the ICCPR to monitor the implementation of the treaty. CCPR conducts periodic reviews of state parties to determine the status of compliance with the Covenant and to act as an intermediary when a state party claims that another state party is in violation of the treaty.

ICCPR has two optional protocols. Optional protocols are additional provisions that state parties to the treaty are not required to adopt but have the option to do so. Once acceded to, however, optional protocols are not provisions that state parties have the “option” of following; they are legally bound by them in the same way they are bound by the provisions of the treaty.

The First Optional Protocol to the ICCPR allows individual citizens or persons within the jurisdiction of a state party to petition the CCPR on alleged state party violations of the Covenant. Because it is much easier for an individual activist to petition the CCPR to call for a change in the abortion laws in one’s own country than it is for the government of one state party invoke its privilege under the treaty to pressure another state party into complying with alleged violations of the treaty, pro-abortion activists have exploited the optional protocol on a number of occasions to advance their ideological agenda. As the CCPR has advocated pro-abortion positions for some time now, the treaty body has become a major conduit for pro-abortion activism on the international stage.

Ireland, as a state party to ICCPR and both of the treaty’s optional protocols, is legally bound by these documents. The United States is a state party to the ICCPR but not to its optional protocols.

Despite the legally binding nature of the Covenant on Ireland, however, neither the ICCPR nor its optional protocols ever mention abortion.

According to Ernie Walton, Director of the Center for Global Justice, Human Rights, and the Rule of Law at the Regent University School of Law, independent states are generally free to act where international law does not explicitly limit it.

“Except for a few minor exceptions, states are free to act except where they limit their ability to act,” Walton says, “the state is sovereign and equal and can only be bound by international law where they give consent, whether through treaties or in cases where states act out of a belief that they have an obligation to do so under international law.”

Rather than asserting a supposed “right” to abortion, the ICCPR guarantees the right to life, declaring that “every human being has the inherent right to life….no one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his life.”[2] State parties to the Covenant must protect these rights for every individual within their jurisdiction without distinction on the status of any kind.[3]

While the CCPR is able to interpret the Covenant, there are limits to the extent to which the Committee can interpret the treaty.

“The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties lays out conditions under which treaties must be interpreted and the Committee is bound, and should be bound, by that,” Walton says.

According to the Vienna Convention on the Laws of Treaties, treaties must be “interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose.”[4] As Ireland and many other state parties to the ICCPR would have never intended at the time of accession that the language of Covenant mandates the legalization of abortion, it is clear that no honest interpretation of the treaty can read any “right” to an abortion into the document. And because abortion cannot be read into the treaty with the “ordinary meaning” given to the terms of the treaty, the fact that Ireland did not express reservations to provisions of the treaty that purportedly mandate the legalization of abortion at the time of accession is immaterial.

On the contrary, it would seem that the ICCPR would have to be interpreted as erring on the side of unborn life. Article 6(5) of the treaty prohibits the death penalty to be carried out on a pregnant woman, a provision that appears to recognize the life of the unborn child.

“On the issue of abortion, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights at best grants a right to life for the unborn and at worst is utterly silent,” Walton says.

What customary international law says about abortion

International law is the rules and norms that apply to several independent states through agreement, practice, or otherwise. International law can be derived from a variety of sources including formal agreements between states such as the ICCPR. International law can also be derived from customary international law, general principles common to the legal systems of various states, or other sources.

Certain norms of international law are said to be peremptory norms (jus cogens). Peremptory norms of international law are standards by which all states must comply without qualification and without exception. No treaty, pattern of law, or formal recognition is needed to enforce them. Actions that violate jus cogens law include crimes such as genocide.

But legalized abortion is clearly not a peremptory norm. And as international agreements such as the ICCPR do not mention abortion and it is not the clear and consistent understanding of states that such treaties obligate states to legalize abortion, could it be argued that Ireland would be required to legalize abortion under its obligations under customary international law?

How customary international law is defined is often subject to debate, but it is generally agreed that it is derived from the “general and consistent practice of states” and that states follow such practice from “a sense of legal obligation.”[5] Customary law can be derived from a variety of sources including the laws and practices of states, treaties, official pronouncements made by governments, the proceedings of international courts and multilateral organizations such as the United Nations, and even (to a lesser extent) the writings and opinions of international law scholars when they are in confluence with the general practice of states.

States, however must provide their consent out of a sense of legal obligation or must fail to dissent at the time such customary law is being developed in order to be bound by it. According to the American Law Institute’s Restatement of the Law (Third), Foreign Relations Law of the United States, “a practice that is generally followed but which states feel legally free to disregard does not contribute to customary law.”[6]

On issue of the legalization of abortion, however, there is hardly any consensus among states.

Under the conditions for abortion legalization outlined by CEDAW—including rape, incest, fetal disability, and physical and mental health—there is no consensus among states that would be binding under customary international law. Currently, a majority (55%) of UN recognized states do not permit abortion under even the minimum conditions stipulated by CEDAW.[7]

“In order for abortion access to be considered a binding obligation under customary international law, we would have to see nearly every country legalize abortion and do so out of some sense of a legal obligation,” Walton says.

In fact, it would seem that the CCPR and other human rights bodies are violating the international consensus on abortion when pressuring the countries to legalize such terminations. According to the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development, a consensus document agreed to by 179 nations at the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in Cairo, “in no case should abortion be promoted as a method of family planning.”[8] States at the ICPD further agreed that the question of abortion legalization lies solely with independent states:

Any measures or changes related to abortion within the health system can only be determined at the national or local level according to the national legislative process.[9]

International law, it would seem, errs heavier on the side of defending the right to life than it does in taking it away. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights declares that “everyone has the right to life.”[10]

The CCPR has even acknowledged that the right to life is a fundamental right, “the supreme right from which no derogation is permitted even in time of public emergency.”[11] It is contrary to CCPR’s own rules to interpret the right to life narrowly:

The expression “inherent right to life” cannot properly be understood in a restrictive manner, and the protection of this right requires that States adopt positive measures.[12]

It would thus appear that it is the mandate of the United Nations Human Right Committee to defend the right to life, rather than to attempt to take it away.

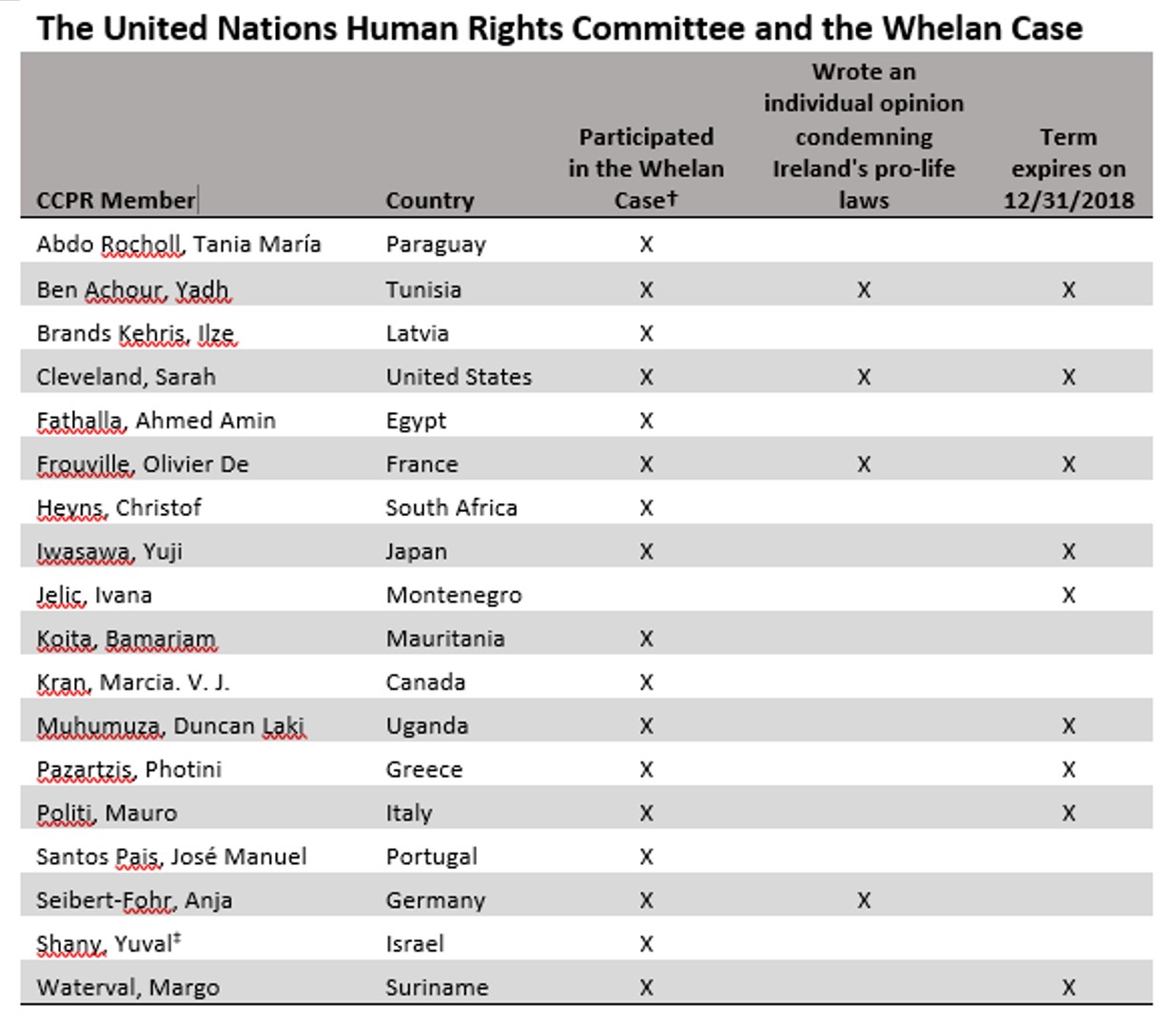

Fortunately, there are ways through the democratic process to remedy the CCPR’s resolve to trample on the inviolable right to life. CCPR members are not elected to serve terms indefinitely. The terms for half of the members that currently sit on the Human Rights Committee expire at the end of next year.

As a great deal of pro-abortion activism at the United Nations comes from the Human Rights Committee, UN member states should seek in earnest to elect well qualified human rights experts that will uphold the principles of national sovereignty, the rule of law, and the right to life for all.

[1] References to “ICCPR,” “Covenant,” or “the treaty” in this article all refer to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

[2] International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, article 6, New York, Dec. 16, 1966 (No. 14668), 999 U.N.T.S. 171.

[3] Ibid, articles 2(1) and 26.

[4] Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, article 31, May 23, 1969 (No. 18232), 1155 U.N.T.S. 331.

[5] Restatement of the Law Third, Foreign Relations Law of the United States §102 (American Law Institute 1987).

[6] Ibid.

[7] This statistic is derived from the status of abortion laws according to: United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2014). Abortion Policies and Reproductive Health around the World. Sales No. E.14.XIII.11. The status of abortion laws since 2013 have been brought up-to-date through Population Research Institute research.

[8] United Nations International Conference on Population and Development (1994). Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development. 13 September. A/CONF.171/13/Rev.1.

[9] Ibid.

[10] United Nations, General Assembly (1948). Universal declaration of human rights, article 3. 10 December. A/RES/217(III).

[11] United Nations, Human Rights Committee (1984). General comment no. 14: article 6 (right to life).

[12] United Nations, Human Rights Committee (1982). General comment no. 6: article 6 (right to life).

LifeNews Note: Jonathan Abbamonte writes for the Population Research Institute.